A Conceptual and Practical introduction to version control

For the dedicated scientist

I would say that the majority of modern science benefits significantly from open-source programs: routines that are freely available for research use, including a transparent code base allowing you to freely inspect and modify it for your own purposes. The great thing with this kind of paradigm is that you can benefit from open-source, and others can benefit from your code being open-source—anyone can stand on your shoulders! 😃

I wrote this post as a means to help scientists to open up their source, and as a general guide to how one can contribute code to an existing Github repository. I don't assume much knowledge, and I'll leave notes on the margin for additional context/explanations outside the main body of text. As always, you can always drop me a line on Twitter or email me!

This article is dedicated to Professor Timothy Barnum—you owe me a Dunkaccino

What is git?

The first thing is to define some nomenclature: likely if you're looking at this post, you'll have heard git and Github used, and because the latter contains the former, maybe to an extent confused as to when the two can be used interchangably.

To clarify, git—as the type used implies—refers to a program: it's a program for managing software versions that was developed as a successor to svm by Linus Torvalds, who is the creator of Linux. As such, most modern UNIX based operating systems will come with git installed. Github, on the other hand, is a cloud platform now owned by Microsoft that serves as an online location where you can host your code repositories A repository can be thought of as a project—it should house all of the things related to that project, including documentation, a description of the code, citation information where relevant, and of course the codebase. , and has grown now to include a lot of nifty automated workflows that lifts a lot of manual work from modern coding like testing, publishing, and hosting. You can use git independently of Github, and indeed there are alternatives: you can always host your own repository service, or use alternatives like GitLab.

Why do I need git in my life?

So how does git benefit scientists? Primarily I see two aspects: first, you can manage—with relative ease At least better than copy pasting a file and appending `v6_final.py` everytime —versions of the code you've written, be it scripts for analyzing data for a specific project, or a general purpose framework like numpy, which lends to scientific reproducibility; second, you can collaborate with your peers, your community, and potentially anyone in the world. The possibility that a project you came up with has the potential to grow into something even you couldn't fathom excites me.

Conceptually, git works by thinking of versions of your code as a tree that grows up:

Here, the circles refer to branches You can think of a branch as a spinoff of the code at a particular point in time: we isolate it so we can work on new things, or just to use it as a point of reference in time. The `main` branch is the typical default name, although in older repositories/`git` versions, it was called `master` branch. , each of the rectangles contains a commit A commit refers to the point codebase that is "saved" in time. , and the arrows indicate the direction of travel between versions.

In the example above, we started off with a codebase, and decided to start using git to track changes we make. We've since added a new feature, fixed what we thought was a typo that turned out to be correct, thereby reverting back to the new feature commit. The fact that this is progressing linearly in one direction means that we can keep track of everything we've done with the code.

Now say someone else wants to help develop your code, perhaps to implement a feature that was useful for their analysis and thought it was helpful for others as well. The proper way to do so involves making a fork:

As seen in the diagram above, a fork A fork is similar to "clone", but differs in that it recreates the repository entirely managed by you and you alone. Because you own the repository, you have full read/write access; conversely, cloning does not give you the same rights. This is important because it means you cannot easily mess up a common code base—there's shared responsibilities! If this doesn't make sense to you, move on and come back to this note after reading the whole post. basically copies all of the code and history from the point in time you performed the action.

You then make the changes that you wanted, and you commit them ("Cool new feature"). At this point, you've diverged from the original repository by one commit. With vanilla git, if you know the author of the original code you could now merge the codebases, and bring the original up to speed with all of the new code. The common way to do so is called a pull request—it's named quite oddly, and so probably deserves some extra attention. To clarify, merging branches is a general term for combining branches of code together. A pull request (PR) specifically asks for the owner of another repository to merge *your* changes to their branch. The name originates from the git command, git request-pull which makes a bit more sense: you ask the owner of another repository to pull the changes from your branch to theirs.

While this example is about as simple as it gets, the main power of git is to recognize which parts of the code is independent of the incoming changes. For example, you might work to add some (very important) documentation in your code, and providing the incoming changes don't modify the existing codebase in any way, you'll be able to work on separate things and still merge them seamlessly:

Even if there are conflicting changes, you can still manually sort through them, and choose which version to keep in the new commit. It might be a bit clumsy in command line to do, but it is possible and other interfaces Including working with the online Github interface, a desktop app like GitKraken, or built-in interfaces in code editors like VS Code. can make this more palatable.

A working example

Now the example above would work, but it's not particularly convenient for you and your collaborator to have to work together to merge the codebase. Services like Github act as a third-party that can perform these tasks asynchronously, and with modern Github, automate a lot of work that might exist for particularly complex codebases. As you might imagine, as your codebase gets increasingly complex, and if more people are involved, it's pretty hard to get everyone together in a room to agree on what changes can be merged and what needs to be revised! That said, it IS possible to do all of these things without a GUI! So, in the interest of providing some practical elements to this post, we'll look at an example workflow of using git (the program) on your computer to make changes to an existing codebase/repository hosted on Github.

Fork the repository you want to work on in Github:

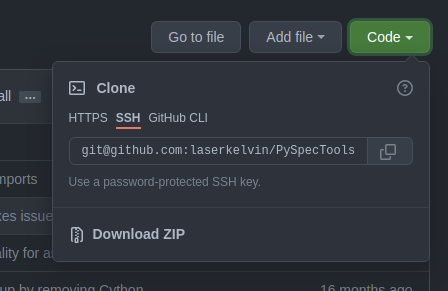

Clone the repository to your computer; we want to make modifications locally. Keep in mind, the best way to clone is to use SSH keys—downloading the zip does not include the extra files that store git repository information, and HTTPS is going to be phased out. A simple alternative is to use a UI like GitKraken or the Github desktop app to do this step.

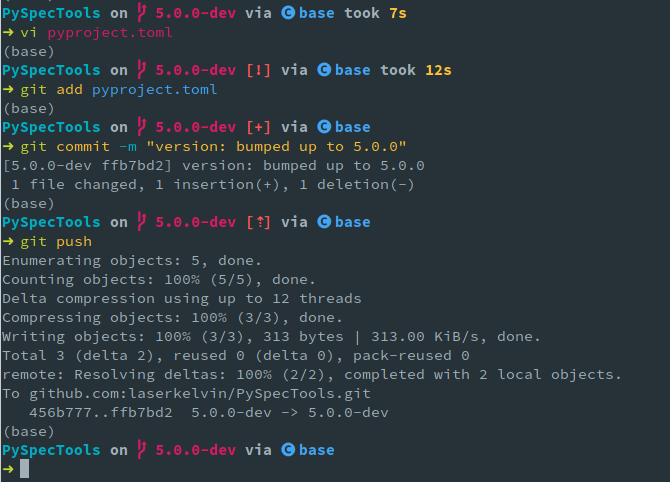

Make the changes you want to files, remembering to keep modifications small between commits, and commit frequently. You will

git addfiles to add them to a stack of files you'll commit, followed bygit committo write a descriptive summary of the things you've changed.

It's probably good to have a mental picture of what the current state of affairs are:

We forked the code from the original repository on Github, cloned the code from our fork, and made changes locally on our computer. We can push our changes back up to our forked repository, to bring the Github version of our code up to the date. I guess this is kind of like syncing Dropbox up to the cloud? Keep in mind, if git push doesn't work, it's likely because you haven't set the "upstream" remote—git doesn't know where to send the changes to: either because there are no remotes set (git remote add <remote name> <link>), or because you haven't set an upstream remote yet (git push --set-upstream <remote name> <branch>). Note that <remote name> by default is origin—this is set if you cloned the repository through the proper means 😉. The whole procedure, in command line, looks like this:

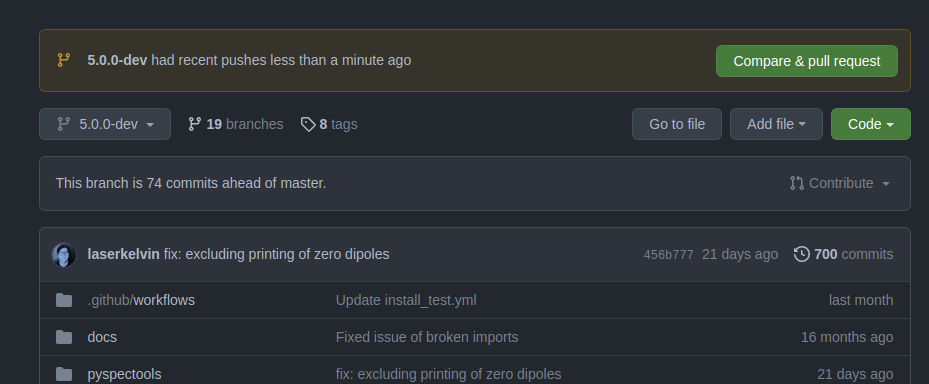

If this step was succesful, you should see changes reflected on Github! Notably, you'll see this banner about a pull request at the top:

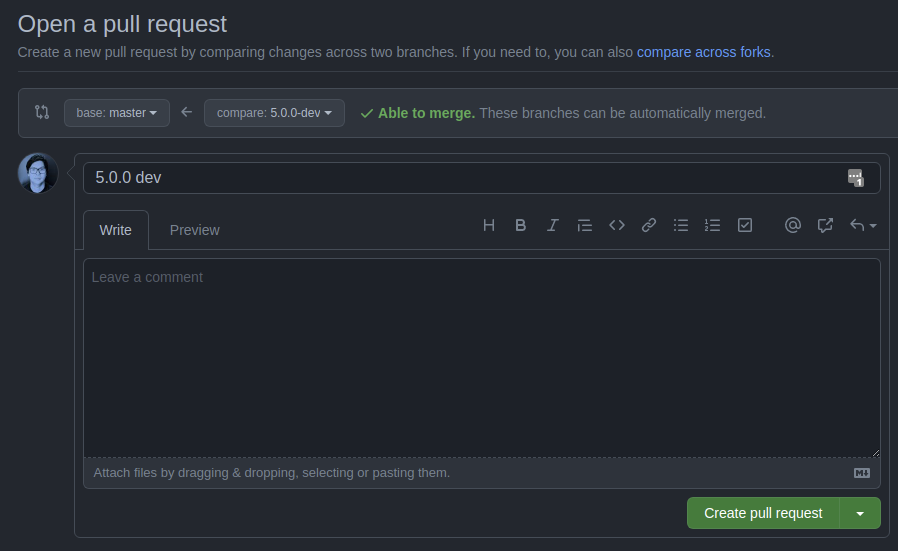

If you were to click on "Compare & pull request, you are then shown this dialog:

What will be shown in the arrow direction will differ for your scenario: if you perform a pull request from a fork, you'll have the option to send the pull request to the owner of the original repository. You should write something descriptive about what is included in your changes, and maintainers of the base repository will review your changes, maybe ask for additional changes, and then (hopefully) merge them into the original codebase.

Appendix

For your convenience, a table of terms used in git related version control.

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Branch | A spinoff of the codebase at a certain point in time |

| Commit | The act of committing your changes to the version history |

| Pull request | To ask the owner of another repository to pull changes from your repository |

| Merge | To combine two branches together |

| Revert | To go back to an earlier commit |

| Checkout | Generally used to revert changes on a file to the last commit. Alternatively with -b, change to a new branch |